Skara Brae is a Neolithic town located in Skaill Bay, next to the town of Sandwick in Mainland, the largest of the Orkney Islands, north of Scotland. It is made up of a set of ten semi-underground stone huts, which has favored its exceptional conservation. Called Scottish Pompeii by some, it is part of a set of prehistoric sites considered a World Heritage Site by UNESCO, under the name of Neolithic Nucleus of Orkney.

The settlement came to light in the winter of 1850. A terrible storm hit the Scottish coast and Orkney, killing 200 people. The storm also swept away the top of a beachfront mound at Skaill Bay on the Mainland, known as Skerrabra. The owner of the land, William Watt, came to inspect the site and noted that the wind had uncovered the tops of several buried stone walls.

The landowner tipped off a local antiquarian, George Petrie, who undertook a technically rather precarious excavation in 1867. Although it was the work of another amateur, Petrie described the constructions in detail, published his findings, and filed a report with the Society. of Antiquaries of Scotland. This publicity gave way to other partial excavations, including those by Balfour Stewart, in 1913 and published in 1914, but also to the visit of looters, who attacked the site in 1914. The site became dependent on the Corona through Her Majesty's Commissioner of Works in 1924.

The authorities decided that it was time to excavate it with modern methods and protect it. Three years later they decided to commission the newly appointed Abercromby Professor of Prehistoric Archeology at the University of Edinburgh, Vere Gordon Childe (1892-1957), to do the work. The professor agreed, but without much enthusiasm, because he considered himself a poor excavator. Which is paradoxical, because today he is considered one of the most outstanding archaeologists in the history of this discipline.

Gordon Childe worked at Skara Brae between 1927 and 1930. As for the excavation, much of his work was emergency intervention. The sea threatened to destroy the site. Assisted by the architect J. Wilson Paterson, his first job was to direct the construction of a protective dam that would prevent the catastrophe and thanks to which the place can still be admired today. In addition, the commission from the authorities was aimed at recovering the place as a monument. In other words, the priority was to clear the cabins and the passageways that join them of sand. The excavation was careful, but has been criticized by later researchers for the small amount of materials that were recovered and preserved.

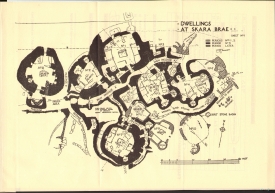

Childe confirmed some of the discoveries of his predecessors and made new discoveries. He excavated ten dwellings, one of which had almost disappeared due to the pounding of the sea. He confirmed that the village had been built inside a mound that is actually a pile of Neolithic debris, an accumulation of shells, bones and other debris, in short, garbage. The walls of the houses were built with stone slabs, in two courses separated by a space also filled with waste, which acted as insulation. In Skara Brae there were no streets. The passages that joined the houses were paved and also covered with stone. They were very low and narrow, a meter high by half a meter wide. The cover of one of the passageways, also made of stone, was preserved intact. All the houses were linked by these entrances, except for one, number 8, which seemed to be the only one that had been a separate construction from the rest.

No trace of the roof of the buildings was found, so Childe deduced that they were covered by perishable materials. The roof of the huts had not been preserved, but their furniture, which was made of stone, had. The distribution was identical in almost all the houses, whose interior space ranged between 20 and 35 square meters. The house plan tends to be round and the interior is irregular, although the larger ones tend to form a square with rounded corners. At the opposite end to the door there is a kind of cupboards that were described by the first excavators as sideboards. Both sides of the access there is the stone base of individual beds. The one on the left is smaller than the one on the right in all cases. Next to the beds are stumps for stone pillars suggesting the use of some kind of canopy or fur curtain to insulate the beds.

In the center there is a place for the fire, flanked by storage boxes delimited with stone slabs. There was no wood in Orkney, so Childe concluded that the inhabitants of Skara Brae relied on logs carried by the tide or used peat for fuel. The lack of wood is a problem when it comes to explaining how the roof could have been. The use of whale bones as supports has been suggested. There are shelves and a drainage system, probably a sink or toilet in almost every house. The huts had a door, and could be closed with a bar that was withdrawn into a hole in the wall. House 8, the isolated one, has no dresser or beds and it seems that it was divided into small cubicles. The most recent investigations have suggested that it could be a workshop for the elaboration of lithic artifacts. One unknown: house 7 is also closed... but from the outside. Why? There's no answer. Both in some points inside the houses and in the passages there is decoration based on linear motifs that in some cases were confused with runes by the first excavators. Decoration is much more abundant in house 8.

Childe concluded that Skara Brae had been a village of ancient shepherds, as he found remains of cattle, goats and sheep. To provide an explanation for the distribution of the beds, he resorted to a comparison with a known and nearby habitat model: the huts of the shepherds of the Highlands of the nineteenth century. In these cabins the men slept separately from the women. The big bed was for the man, the small one for the woman.

But Childe's main discovery was to demonstrate that the site had experienced several stages of occupation, of which he came to distinguish four through the study of stratigraphy. Skara Brae, was what remained of the remains of an accumulation of various habitats. The oldest houses - numbers 9 and 10 - were very different from the most recent ones, as the Australian archaeologist observed. In the old ones, the furniture (beds and dressers) are installed in holes in the walls; in the recent ones, which are somewhat larger, they project from the walls. In addition, the old houses were not connected by passages and in the earliest Skara Brae there was a common open space which Childe called a market. The first Skara Brae must have been very different from what is seen today, an exotic semi-subterranean village, and more like a conventional village of huts arranged around an open space.

The archaeologist carried out several surveys and found that below the Skara Brae now in view, structures of the oldest are preserved. The two indicated houses are still visible because no others were built on top of them. In his opinion, there was a Skara Brae 1, on which a Skara Brae 2 was built -formed by the oldest preserved huts, 9 and 10, and parts of 3 and 4-. Skara Brae 3 was built on top and some final additions would form Skara Brae 4. According to Childe. "the flimsy shacks of Skara Brae 2 need not have been inhabited for a long period of time. They would be progressively replaced by larger, more solid buildings, perhaps starting with shack number 7. Consequently, its wall materials were reused in the most modernized cabins, and the emplacements of the old ones leveled”.

In the excavations carried out years later, samples dated using the C-14 method were obtained. The dates showed that the town had been inhabited between 3180 and 2500 BC. Skara Brae is older than the pyramids of Giza and Stonehenge. It is an exceptionally well preserved Neolithic village due to the sand that covered it after it was abandoned.

Excavations in 1972, led by D. V. Clarke, showed that the villagers were farmers as well as herders, growing barley and wheat. At its height, the village must have consisted of seven or eight huts, inhabited by about 50 people in all. At that time the coast was much further away and the town was in the middle of a meadow. Its appearance must have been that of a grassy mound from which the roofs of the houses would protrude, probably also covered with grass. For a long time it was believed that Skara Brae had disappeared under the sand during a storm, hence the analogy with Pompeii. The main hypothesis was that the village succumbed to a catastrophe. The inhabitants of the huts were forced to flee their homes, abandoning on the shelves and on the floor many of their possessions, made with great work and industriousness. But it has been shown that its inhabitants abandoned it and that its burial was a very long process. The cause of the abandonment? It is ignored.

The settlement came to light in the winter of 1850. A terrible storm hit the Scottish coast and Orkney, killing 200 people. The storm also swept away the top of a beachfront mound at Skaill Bay on the Mainland, known as Skerrabra. The owner of the land, William Watt, came to inspect the site and noted that the wind had uncovered the tops of several buried stone walls.

The landowner tipped off a local antiquarian, George Petrie, who undertook a technically rather precarious excavation in 1867. Although it was the work of another amateur, Petrie described the constructions in detail, published his findings, and filed a report with the Society. of Antiquaries of Scotland. This publicity gave way to other partial excavations, including those by Balfour Stewart, in 1913 and published in 1914, but also to the visit of looters, who attacked the site in 1914. The site became dependent on the Corona through Her Majesty's Commissioner of Works in 1924.

The authorities decided that it was time to excavate it with modern methods and protect it. Three years later they decided to commission the newly appointed Abercromby Professor of Prehistoric Archeology at the University of Edinburgh, Vere Gordon Childe (1892-1957), to do the work. The professor agreed, but without much enthusiasm, because he considered himself a poor excavator. Which is paradoxical, because today he is considered one of the most outstanding archaeologists in the history of this discipline.

Gordon Childe worked at Skara Brae between 1927 and 1930. As for the excavation, much of his work was emergency intervention. The sea threatened to destroy the site. Assisted by the architect J. Wilson Paterson, his first job was to direct the construction of a protective dam that would prevent the catastrophe and thanks to which the place can still be admired today. In addition, the commission from the authorities was aimed at recovering the place as a monument. In other words, the priority was to clear the cabins and the passageways that join them of sand. The excavation was careful, but has been criticized by later researchers for the small amount of materials that were recovered and preserved.

Childe confirmed some of the discoveries of his predecessors and made new discoveries. He excavated ten dwellings, one of which had almost disappeared due to the pounding of the sea. He confirmed that the village had been built inside a mound that is actually a pile of Neolithic debris, an accumulation of shells, bones and other debris, in short, garbage. The walls of the houses were built with stone slabs, in two courses separated by a space also filled with waste, which acted as insulation. In Skara Brae there were no streets. The passages that joined the houses were paved and also covered with stone. They were very low and narrow, a meter high by half a meter wide. The cover of one of the passageways, also made of stone, was preserved intact. All the houses were linked by these entrances, except for one, number 8, which seemed to be the only one that had been a separate construction from the rest.

No trace of the roof of the buildings was found, so Childe deduced that they were covered by perishable materials. The roof of the huts had not been preserved, but their furniture, which was made of stone, had. The distribution was identical in almost all the houses, whose interior space ranged between 20 and 35 square meters. The house plan tends to be round and the interior is irregular, although the larger ones tend to form a square with rounded corners. At the opposite end to the door there is a kind of cupboards that were described by the first excavators as sideboards. Both sides of the access there is the stone base of individual beds. The one on the left is smaller than the one on the right in all cases. Next to the beds are stumps for stone pillars suggesting the use of some kind of canopy or fur curtain to insulate the beds.

In the center there is a place for the fire, flanked by storage boxes delimited with stone slabs. There was no wood in Orkney, so Childe concluded that the inhabitants of Skara Brae relied on logs carried by the tide or used peat for fuel. The lack of wood is a problem when it comes to explaining how the roof could have been. The use of whale bones as supports has been suggested. There are shelves and a drainage system, probably a sink or toilet in almost every house. The huts had a door, and could be closed with a bar that was withdrawn into a hole in the wall. House 8, the isolated one, has no dresser or beds and it seems that it was divided into small cubicles. The most recent investigations have suggested that it could be a workshop for the elaboration of lithic artifacts. One unknown: house 7 is also closed... but from the outside. Why? There's no answer. Both in some points inside the houses and in the passages there is decoration based on linear motifs that in some cases were confused with runes by the first excavators. Decoration is much more abundant in house 8.

Childe concluded that Skara Brae had been a village of ancient shepherds, as he found remains of cattle, goats and sheep. To provide an explanation for the distribution of the beds, he resorted to a comparison with a known and nearby habitat model: the huts of the shepherds of the Highlands of the nineteenth century. In these cabins the men slept separately from the women. The big bed was for the man, the small one for the woman.

But Childe's main discovery was to demonstrate that the site had experienced several stages of occupation, of which he came to distinguish four through the study of stratigraphy. Skara Brae, was what remained of the remains of an accumulation of various habitats. The oldest houses - numbers 9 and 10 - were very different from the most recent ones, as the Australian archaeologist observed. In the old ones, the furniture (beds and dressers) are installed in holes in the walls; in the recent ones, which are somewhat larger, they project from the walls. In addition, the old houses were not connected by passages and in the earliest Skara Brae there was a common open space which Childe called a market. The first Skara Brae must have been very different from what is seen today, an exotic semi-subterranean village, and more like a conventional village of huts arranged around an open space.

The archaeologist carried out several surveys and found that below the Skara Brae now in view, structures of the oldest are preserved. The two indicated houses are still visible because no others were built on top of them. In his opinion, there was a Skara Brae 1, on which a Skara Brae 2 was built -formed by the oldest preserved huts, 9 and 10, and parts of 3 and 4-. Skara Brae 3 was built on top and some final additions would form Skara Brae 4. According to Childe. "the flimsy shacks of Skara Brae 2 need not have been inhabited for a long period of time. They would be progressively replaced by larger, more solid buildings, perhaps starting with shack number 7. Consequently, its wall materials were reused in the most modernized cabins, and the emplacements of the old ones leveled”.

In the excavations carried out years later, samples dated using the C-14 method were obtained. The dates showed that the town had been inhabited between 3180 and 2500 BC. Skara Brae is older than the pyramids of Giza and Stonehenge. It is an exceptionally well preserved Neolithic village due to the sand that covered it after it was abandoned.

Excavations in 1972, led by D. V. Clarke, showed that the villagers were farmers as well as herders, growing barley and wheat. At its height, the village must have consisted of seven or eight huts, inhabited by about 50 people in all. At that time the coast was much further away and the town was in the middle of a meadow. Its appearance must have been that of a grassy mound from which the roofs of the houses would protrude, probably also covered with grass. For a long time it was believed that Skara Brae had disappeared under the sand during a storm, hence the analogy with Pompeii. The main hypothesis was that the village succumbed to a catastrophe. The inhabitants of the huts were forced to flee their homes, abandoning on the shelves and on the floor many of their possessions, made with great work and industriousness. But it has been shown that its inhabitants abandoned it and that its burial was a very long process. The cause of the abandonment? It is ignored.